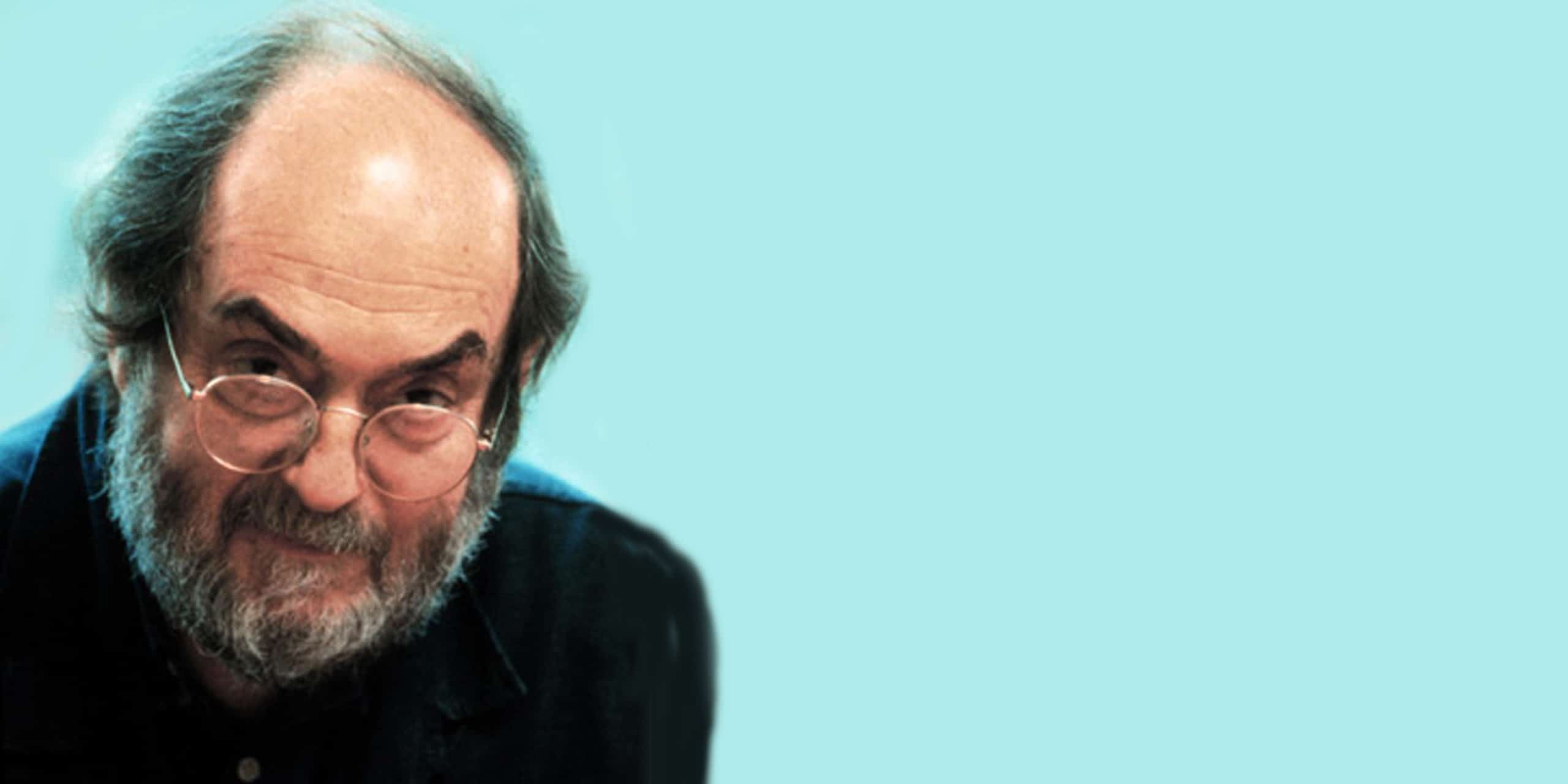

Stanley Kubrick net worth is $20 Million. Also know about Stanley Kubrick bio, salary, height, age weight, relationship and more …

Stanley Kubrick Wiki Biography

Stanley Kubrick was born on the 26th July 1928, in Manhattan, New York City USA, and was a film director, producer, screenwriter, cinematographer, editor, and photographer, but best known for directing such movies as “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968), “A Clockwork Orange” (1971), “The Shining” (1980) and “Full Metal Jacket” (1987). Kubrick won an Oscar, two BAFTA’s, and was nominated for four Golden Globe awards. His career started in 1951 and ended in 1999, when he passed away.

Have you ever wondered how rich Stanley Kubrick was, at the time of his death? According to authoritative sources, it has been estimated that Stanley Kubrick’s net worth was as high as $20 million, an amount earned through his successful career largely as a director. In addition to being one of the best directors of our time, Kubrick was also involved in other aspects of cinematography, which improved his wealth too.

Stanley Kubrick was the elder of two children of Sadie Gertrude and Jacob Leonard Kubrick; and although they were Jewish, Stanley did not have a religious upbringing. He went to Public School 3 and later to Public School 90 in the Bronx. Although his IQ proved to be above average, Stanley didn’t do well in school, and his grades were poor. He did develop an interest in literature, especially Roman and Greek mythology and the Grimm brothers’ stories.

Kubrick went to the William Howard Taft High School from 1941 to 1945 and was an official school photographer for a year. He sold a set of photographs to Look magazine for $30, and also played chess in local chess clubs to supplement his income. Kubrick’s first short film “Flying Padre” came out in 1951, and “Day of the Fight” followed in the same year. In 1953, Stanley made his debut feature film called “Fear and Desire”, then “Killer’s Kiss” (1955), and “The Killing” (1956) which earned him a BAFTA nomination and received excellent critiques. His next movie, “Paths of Glory” (1957) starring Kirk Douglas, was a huge success and helped Kubrick to establish himself as one of the brightest directors at the time, adding to his net worth.

In 1960, Stanley teamed up again with Douglas in “Spartacus” which won four Oscars and grossed over $60 million, which was an enormous amount of money back then. Two years later, Kubrick filmed the Oscar-nominated “Lolita” with James Mason, Shelley Winters, and Sue Lyon – the film didn’t have great commercial success but was quite popular among the critics and viewers. In 1964, Stanley made one of the best comedy movies ever – “Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb” starring Peter Sellers, George C. Scott, and Sterling Hayden. It received four Oscar nominations and grossed over $10 million with a budget of $1.8 million.

In 1968, he made one of the unique sci-fi movies of our time entitled “2001: A Space Odyssey” with Keir Dullea, Gary Lockwood, and William Sylvester, and Kubrick won his only Oscar for Best Effects, Special Visual Effects, but was not present at the ceremony, so the presenters Diahann Carroll and Burt Lancaster accepted the award on his behalf. Although the movie’s budget was $12 million, it managed to gross over $55 million and made Kubrick a very rich man. Stanley’s next movie was one of the most controversial in the history of cinema and raised a lot of eyebrows, especially in the UK; “A Clockwork Orange” (1971) with Malcolm McDowell, Patrick Magee, and Michael Bates is a story about a group of delinquents and the experimental therapy which was supposed to solve society’s crime problem. The film received four Oscar nominations, including the Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Writing, Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium. With the budget of $2.2 million, it grossed more than $25 million and significantly improved Kubrick’s net worth.

In 1975, Kubrick released the historical drama “Barry Lyndon” starring Ryan O’Neal, Marisa Berenson, and Patrick Magee – Stanley spent a lot of money on its production ($11 million), but managed to gross over $30 million and win four Oscars and earn three more nominations. Kubrick collaborated with the novelist Stephen King to create one of the scariest horror movies to date – “The Shining” (1980) with Jack Nicholson, Shelley Duvall, and Danny Lloyd. He used $19 million for the filming while earned almost $45 million at the box office. In 1987, Kubrick made the highly acclaimed war drama called “Full Metal Jacket” starring Matthew Modine, R. Lee Ermey, and Vincent D’Onofrio, and received one Oscar nomination for Best Writing, Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium.

Stanley had a break in directing that lasted 12 years before created his last movie “Eyes Wide Shut” (1999) starring Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman. He died only six days after the completion of the film.

Regarding his personal life, was married to Toba Metz from 1948 to 1951, and then to the Austrian-born dancer and theatrical designer Ruth Sobotka from 1955 to 1957. He was in a relationship with actress Valda Setterfield before he married the German actress Christiane Harlan in 1958 and stayed with her until his death from a heart attack on the 7th March 1999 in Harpenden, Hertfordshire, England; they had two daughters together.

IMDB Wikipedia $20 million 1928 1928-7-26 1999-03-07 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) 5′ 6½” (1.69 m) A Clockwork Orange (1971) American Anya Anya Kubrick Barbara Kubrick Burt Lancaster Christiane Kubrick (m. 1958–1999) Christiane Kubrick Ruth Sobotka Toba Kubrick City College of New York Columbia University Danny Lloyd Diahann Carroll Director Film director Full Metal Jacket (1987) Gary Lockwood George C. Scott Gertrude Kubrick Jack Nicholson Jacques Leonard Kubrick James Mason July 26 Katharina Kubrick Katherina Keir Dullea Kirk Douglas Leo Malcolm McDowell Manhattan Marisa Berenson Matthew Modine Michael Bates New York Nicole Kidman Patrick Magee Peter Sellers producer R. Lee Ermey Ruth Sobotka (m. 1955–1957) Ryan O’Neal Shelley Duvall Shelley Winters Stanley Kubrick Stanley Kubrick Net Worth Stephen King Sterling Hayden Sue Lyon The Shining (1980) Toba Metz (m. 1948–1951) Tom Cruise United States Vincent D’Onofrio Vivian Kubrick William Howard Taft High School William Sylvester Writer

Stanley Kubrick Quick Info

| Full Name | Stanley Kubrick |

| Net Worth | $20 Million |

| Date Of Birth | July 26, 1928 |

| Died | 1999-03-07 |

| Place Of Birth | Manhattan, New York, United States |

| Height | 5′ 6½” (1.69 m) |

| Profession | Film director, screenwriter, producer, cinematographer, editor, photographer |

| Education | William Howard Taft High School, Columbia University, City College of New York |

| Nationality | American |

| Spouse | Christiane Kubrick (m. 1958–1999), Ruth Sobotka (m. 1955–1957), Toba Metz (m. 1948–1951) |

| Children | Vivian Kubrick, Anya Kubrick, Katharina Kubrick |

| Parents | Gertrude Kubrick, Jacques Leonard Kubrick |

| Siblings | Barbara Kubrick |

| IMDB | http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0000040/ |

| Allmusic | http://www.allmusic.com/artist/stanley-kubrick-mn0001621156 |

| Awards | Hugo Awards – Best Dramatic Presentation, Academy Award for best visual effects, British Academy Film Awards for for Best British Film, for Best Direction, BAFTA Award for Best British Film, Golden Globe Awards for Best Motion Picture – Drama (1961),Locarno International Film Festival Prize for Be… |

| Nominations | Academy Award for Best Director, Academy Award for Best Picture, Academy Award for Best Writing Adapted Screenplay, Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay, Golden Lion, Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama, Golden Globe Award for Best Director – Motion Picture, César Award for B… |

| Movies | “Paths of Glory” (1957), “Fear and Desire”, “One-Eyed Jacks” (1961), “Spartacus” (1961), “Lolita” (1962), “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1969), “Justified”, “Suits”, “Inherent Vice”, “Six Gun Savior”, “A Clockwork Orange” (1972), “Lolita” (1963) |

Stanley Kubrick Trademarks

- Often cast ‘Peter Sellers’, ‘Kirk Douglas’, and ‘Philip Stone’

- Slow, methodical tracking shots

- Slow-paced dialogue; often had actors pause several beats between line delivery. Also, rarely (if ever) did his dialogue overlap.

- Very strong visual style with heavy emphasis on symbolism

- His films often tackle controversial social themes

- More often than not sports a long beard

- Often features mellow, emotionally distant characters

- Frequently uses strong primary colors in his cinematography and sharp contrast between black and white.

- Almost all of his films involve a plan that goes horribly wrong

- [Duality] Kubrick’s last five films, minus The Shining (1980), are structurally split into two distinct halves, most likely to mimic the nature of duality in the characters of his films. For example, A Clockwork Orange (1971) shows Alex (Malcolm McDowell) as a sadistic rapist and murderer in the first half of the film and a mind-controlled guinea pig in the second half. In Eyes Wide Shut (1999), Bill (Tom Cruise) travels amidst sexual temptation in New York at night in the first half of the film and rude awakenings during the day in the second half.

- Preferred mono sound over stereo. Only three of his movies – Spartacus (1960), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and Eyes Wide Shut (1999) – were originally done in stereo sound.

- [Dark humor] All of Kubrick’s films, especially “Dr. Strangelove”, have elements of black humor in them.

- Often uses music to work against on-screen images to create a sense of irony. In A Clockwork Orange (1971), Alex sings “Singin’ in the Rain” while raping Mrs. Alexander. In Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), images of nuclear holocaust are accompanied by the song “We’ll Meet Again”. The final scene in Full Metal Jacket (1987) has the battle hardened Marines singing the theme to “The Mickey Mouse Club”.

- All of his films end with “The End”, when this became out of style in later years because of the need to run end credits, he moved “The End” to the end of the credits.

- In almost every movie he made, there is a tracking shot of a character (the camera following the character).

- Varies aspect ratios in a single film. Apparent in Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964) and A Clockwork Orange (1971).

- Credits are always a slide show. He never used rolling credits except for the opening of The Shining (1980).

- [First-person] Uses the first person viewpoint (the character’s perspective) at least once in each film.

- One of his signature shots was “The Glare” – a character’s emotional meltdown is depicted by a close-up shot of the actor with his head tilted slightly down, but with his eyes looking up – usually directly into the camera. Examples are the opening shot of Alex in A Clockwork Orange (1971), Jack slowly losing his mind in The Shining (1980), Pvt. Pyle going mad in Full Metal Jacket (1987) and Tom Cruise’s paranoid thoughts inside the taxicab in Eyes Wide Shut (1999). Even HAL-9000 has “The Glare” in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

- Preferred to shoot his films in the Academy ratio (1.37:1). The exceptions were: Spartacus (1960), in Panavision, and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), in Cinerama. Much of his films consist of wide-angle shots that give the impression of a wide-screen movie, wide up-and-down as well as wide sideways. From The Killing (1956) onward, his films looked increasingly odder, bigger, and more properly viewed from the rows closer to the screen.

- In his last seven films almost always used previously composed music (such as The Blue Danube andThus Spake Zarathustra in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968))

- Involves his wives in his movies. His first wife, Toba Etta Metz Kubrick, was the dialogue director for Stanley’s first feature film Fear and Desire (1953). His second wife, Ruth Sobotka Kubrick, was in Killer’s Kiss (1955) as a ballet dancer named Iris in a short sequence for which she also did the choreography. Kubrick’s third, and final, wife, Christiane Harlan Kubrick, appeared (as Susanne Christian) in Paths of Glory (1957) before she married him as the only female character (a German singing girl) in the movie. She also did some of the now-infamous paintings for A Clockwork Orange (1971) and some more for Eyes Wide Shut (1999). In addition, her brother, Jan, was Stanley’s assistant for A Clockwork Orange (1971) and the executive producer for all of Kubrick’s films starting with Barry Lyndon (1975) and going through The Shining (1980), Full Metal Jacket (1987) and Eyes Wide Shut (1999). Also, his daughter, Vivian Kubrick, is the little girl who asks for a Bush Baby for her birthday in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

- [Beginning Voice-over] Paths of Glory (1957), Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964) and A Clockwork Orange (1971) all begin with a voice over, and The Killing (1956) features narration.

- Known for his exorbitant shooting ratio and endless takes, he reportedly exposed an incredible 1.3 million feet of film while shooting The Shining (1980), the release print of which runs for 142 minutes. Thus, he used less than 1% of the exposed film stock, making his shooting ratio an indulgent 102:1 when a ratio of 5 or 10:1 is considered the norm.

- [Bathroom] All of Kubrick’s films feature a pivotal scene that takes place in a bathroom.

- [CRM 114] He often uses the sequence CRM114 in serial numbers. CRM-114 is the name of the decoder in Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), the Jupiter explorer’s “licence plate number” in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) is CRM114, and in A Clockwork Orange (1971) Alex is given “Serum 114” when he undergoes the Ludovico treatment.

- [Faces] Extreme close-ups of intensely emotional faces

- [Three-way] Constructs three-way conflicts

- [Symmetry] Symmetric image composition. Often features shots down the length of tall, parallel walls, e.g. the head in Full Metal Jacket (1987), the maze and hotel coridors in The Shining (1980) and the computer room in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

- His films often tell about the dark side of human nature, especially dehumanization.

- Adapted every film he made from a novel, excluding his first two films: Killer’s Kiss (1955) and Fear and Desire (1953) (both from original source material), and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

- [Narration] Nearly all of his films contain a narration at some point (2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)) contains narration in the screenplay, as does the screenplay for Eyes Wide Shut (1999), and The Shining (1980) has some sparse title cards.

Stanley Kubrick Quotes

- One of the attractions of a war or crime story is that it provides an almost unique opportunity to contrast an individual of our contemporary society with a solid framework of accepted value, which the audience becomes fully aware of, and which can be used as a counterpoint to a human, individual, emotional situation. Further, war acts as a kind of hothouse for forced, quick breeding of attitudes and feelings. Attitudes crystallize and come out into the open. Conflict is natural, when it would in a less critical situation have to be introduced almost as a contrivance, and would thus appear forced, or- even worse- false.

- In making a film, I start with an emotion, a feeling, a sense of a subject or a person or a situation. The theme and technique come as a result of the material passing, as it were, through myself and coming out of the projector lens. It seems to me that simply striving for a genuinely personal approach, whatever it may be, is the goal- Bergman and Fellini, for example, although perhaps as different in their outlook as possible, have achieved this, and I’m sure it is what gives their films an emotional involvement lacking in most work.

- What I like about not writing original material- which I’m not even certain I could do- is that you have this tremendous advantage of reading something for the first time. You never have this experience again with the story. You have a reaction to it: it’s a kind of falling-in-love reaction. That’s the first thing. Then it becomes almost a matter of code breaking, of breaking the work down into a structure that is truthful, that doesn’t lose the ideas or the content or the feeling of the book. And fitting it all into the much more limited time frame of a movie. And as long as you possibly can, you retain your emotional attitude, whatever it was that made you fall in love in the first place. You judge a scene by asking yourself, “Am I still responding to what’s there?” The process is both analytical and emotional. You’re trying to balance calculating analysis against feeling. And it’s almost never a question “What does this scene mean?” It’s “Is this truthful, or does something about it feel false?” It’s “Is this scene interesting? Will it make me feel the way I felt when I first fell in love with the material?” It’s an intuitive process, the way I imagine writing music is intuitive. It’s not a matter of structuring an argument.

- [on his early career- starting with Fear and Desire (1953)] A pretentious, inept and boring film- a youthful mistake costing about 50,000 dollars- but it was distributed by Joseph Burstyn, in the art houses and caused a little ripple of publicity and attention… I mean there were people around who found some good things in it, and on the strength of that I was able to raise private financing to make a second feature-length film, Killer’s Kiss. And that was a silly story too, but my concern was still in getting experience and simply functioning in the medium, so the content of a story seemed secondary to me. I just took the line of least resistance, whatever story came to hand. And for another thing I had no money to live on at the time, much less to buy good story material with- nor did I have the time to work it into shape- and I didn’t want to take a job, and get off the track, so I had to keep moving.

- [on what advantages film has over other media] Well, for one thing I think it is fairly obvious that the events and situations that are most meaningful to people are those in which they are actually involved- and I’m convinced that this sense of personal involvement derives in large part from visual perception. I once saw a woman hit by a car, for example, or right after she had been hit, and she was lying in the middle of the road. I knew that at that moment I would have risked my life if necessary to help her… whereas if I had merely read about the accident or heard about it, it could not have meant too much. Of all the creative media I think that film is most nearly able to convey this sense of meaningfulness; to create an emotional involvement and a feeling of participation in the person seeing it.

- Man isn’t a noble savage, he’s an ignoble savage. He is irrational, brutal, weak, silly, unable to be objective about anything where his own interests are involved- that about sums it up. I’m interested in the brutal and violent nature of man because it’s a true picture of him. And any attempt to create social institutions on a false view of the nature of man is probably doomed to failure.

- [on Schindler’s List (1993)] Think that’s about the Holocaust? That was about success, wasn’t it? The Holocaust is about six million people who get killed. Schindler’s List is about 600 who don’t.

- 2001 would give a little insight into my metaphysical interests. I’d be very surprised if the universe wasn’t full of an intelligence of an order that to us would seem God-like. I find it very exciting to have a semi-logical belief that there’s a great deal to the universe we don’t understand, and that there is an intelligence of an incredible magnitude outside the Earth. It’s something I’ve become more and more interested in. I find it a very exciting and satisfying hope.

- [on film critics] I find a lot of critics misunderstand my films; probably everybody’s films. Very few of them spend enough time thinking about them. They look at the film once, they don’t really remember what they saw, and they write the review in an hour. I mean, one spent more time on a book report in school.

- A great story is kind of a miracle. I’ve never written a story myself, which is probably why I have so much respect for it. I started out, before I became a film director, always thinking, you know, if I couldn’t play on the Yankees I’d like to be a novelist. The people I first admired were not film directors but novelists. Like Conrad.

- [explaining his hatred of interviews] There is always the problem of being misquoted or, what’s even worse, of being quoted exactly.

- A director can’t get anything out of an actor that he doesn’t already have. You can’t start an acting school in the middle of making a film.

- Music is one of the most effective ways of preparing an audience and reinforcing points that you wish to impose on it. The correct use of music, and this includes the non-use of music, is one of the great weapons that the filmmaker has at his disposal.

- One of the things that I always find extremely difficult, when a picture’s finished, is when a writer or a film reviewer asks, “Now, what is it that you were trying to say in that picture?” And without being thought too presumptuous for using this analogy, I like to remember what T.S. Eliot said to someone who had asked him – I believe it was about The Waste Land – what he meant by the poem. He replied, “I meant what it said.” If I could have said it any differently, I would have.

- I think aesthetically recording spontaneous action, rather than carefully posing a picture, is the most valid and expressive use of photography.

- I’ve never been certain whether the moral of the Icarus story should only be, as is generally accepted, ‘don’t try to fly too high’, or whether it might also be thought of as ‘forget the wax and feathers, and do a better job on the wings’.

- [on The Shining (1980)] I’ve always been interested in ESP and the paranormal. In addition to the scientific experiments which have been conducted suggesting that we are just short of conclusive proof of its existence, I’m sure we’ve all had the experience of opening a book at the exact page we’re looking for, or thinking of a friend a moment before they ring on the telephone. But The Shining didn’t originate from any particular desire to do a film about this. I thought it was one of the most ingenious and exciting stories of the genre I had read. It seemed to strike an extraordinary balance between the psychological and the supernatural in such a way as to lead you to think that the supernatural would eventually be explained by the psychological: “Jack must be imagining these things because he’s crazy.” This allowed you to suspend your doubt of the supernatural until you were so thoroughly into the story that you could accept it almost without noticing. The novel is by no means a serious literary work, but the plot is for the most part extremely well worked out, and for a film that is often all that really matters.

- [on Barry Lyndon (1975)] Ryan O’Neal was the best actor for the part. He looked right and I was confident that he possessed much greater acting ability than he had been allowed to show in many of the films he had previously done. In retrospect, I think my confidence in him was fully justified by his performance, and I still can’t think of anyone who would have been better for the part. The personal qualities of an actor, as they relate to the role, are almost as important as his ability, and other actors, say like Al Pacino, Jack Nicholson or Dustin Hoffman, just to name a few who are great actors, would nevertheless have been wrong to play Barry Lyndon. I liked Ryan and we got along very well together.

- From the very beginning, all of my films have divided the critics. Some have thought them wonderful, and others have found very little good to say. But subsequent critical opinion has always resulted in a very remarkable shift to the favorable. In one instance, the same critic who originally rapped the film has several years later put it on an all-time best list. But of course, the lasting and ultimately most important reputation of a film is not based on reviews, but on what, if anything, people say about it over the years, and on how much affection for it they have.

- I can’t honestly say what led me to make any of my films. The best I can do is to say I just fell in love with the stories. Going beyond that is a bit like trying to explain why you fell in love with your wife: she’s intelligent, has brown eyes, a good figure. Have you really said anything? Since I am currently going through the process of trying to decide what film to make next, I realize just how uncontrollable is the business of finding a story, and how much it depends on chance and spontaneous reaction. You can say a lot of “architectural” things about what a film story should have: a strong plot, interesting characters, possibilities for cinematic development, good opportunities for the actors to display emotion, and the presentation of its thematic ideas truthfully and intelligently. But of course, that still doesn’t really explain why you chose something, nor does it lead you to a story. You can only say that you probably wouldn’t choose a story that doesn’t have most of those qualities.

- The feel of the experience is the important thing, not the ability to verbalize or analyze it.

- [on why he decided to make ‘Dr. Strangelove’ as a comedy] As I kept trying to imagine the way in which things would really happen, ideas kept coming to me which I would discard because they were so ludicrous. I kept saying to myself: ‘I can’t do this. People will laugh.’

- [on Jack Nicholson] I believe that Jack is one of the best actors in Hollywood, perhaps on a par with the greatest stars of the past like Spencer Tracy and James Cagney. I should think that he is on almost everyone’s first-choice list for any role which suits him. His work is always interesting, clearly conceived and has the X-factor, magic. Jack is particularly suited for roles which require intelligence. He is an intelligent and literate man, and these are qualities almost impossible to act. In The Shining (1980), you believe he’s a writer, failed or otherwise.

- One of the things that gave me the most confidence in trying to make a film was seeing all the lousy films that I saw. Because I sat there and thought, Well, I don’t know a goddamn thing about movies, but I know I can make a film better than that.

- Part of my problem is that I cannot dispel the myths that have somehow accumulated over the years. Somebody writes something, it’s completely off the wall, but it gets filed and repeated until everyone believes it. For instance, I’ve read that I wear a football helmet in the car.

- There are very few directors, about whom you’d say you automatically have to see everything they do. I’d put Fellini, Bergman and David Lean at the head of my first list, and Truffaut at the head of the next level.

- [on why he chose Shelley Duvall for The Shining (1980)] I had seen all of her films and greatly admired her work. I think she brought an instantly believable characterization to her part. The wonderful thing about Shelley is her eccentric quality. The way she talks, the way she moves, the way her nervous system is put together. Shelley seemed to be exactly the kind of woman who would marry someone like Jack and be stuck with him.

- There’s something inherently wrong with the human personality. There’s an evil side to it. One of the things that horror stories can do is to show us the archetypes of the unconscious: we can see the dark side without having to confront it directly. Also, ghost stories appeal to our craving for immortality. If you can be afraid of a ghost, then you have to believe that a ghost may exist. And if a ghost exists, then oblivion might not be the end.

- Eisenstein does it with cuts, Max Ophuls does it with fluid movement. Chaplin does it with nothing. Eisenstein seems to be all form and no content, Chaplin is all content and little form. Nobody could have shot a film in a more pedestrian way than Chaplin. Nobody could have paid less attention to story than Eisenstein. Alexander Nevsky is, after all, a pretty dopey story. Potemkin is built around a heavy propaganda story. But both are great filmmakers.

- The essence of dramatic form is to let an idea come over people without it being plainly stated. When you say something directly, it’s simply not as potent as it is when you allow people to discover it for themselves.

- Observancy is a dying art.

- I do not always know what I want, but I do know what I don’t want.

- [Why he shoots so many takes] Because actors don’t know their lines.

- [on Charles Chaplin] Chaplin is all content and little form. Nobody could have shot a film in a more pedestrian way than Chaplin.

- Sanitized violence in movies has been accepted for years. What seems to upset everybody now is the showing of the consequences of violence.

- To make a film entirely by yourself, which initially I did, you may not have to know very much about anything else, but you must know about photography.

- I have a wife, three children, three dogs, seven cats. I’m not a Franz Kafka, sitting alone and suffering.

- [on An Officer and a Gentleman (1982)] I think Louis Gossett Jr.’s performance was wonderful, but he had to do what he was given in the story. The film clearly wants to ingratiate itself with the audience. So many films do that. You show the drill instructor really has a heart of gold – the mandatory scene where he sits in his office, eyes swimming with pride about the boys and so forth. I suppose he actually is proud, but there’s a danger of falling into what amounts to so much sentimental bullshit.

- I don’t mistrust sentiment and emotion, no. The question becomes, ‘Are you giving them something to make them a little happier, or are you putting in something that is inherently true to the material?’ Are people behaving the way we all really behave, or are they behaving the way we would like them to behave? I mean, the world is not as it’s presented in Frank Capra films. People love those films – which are beautifully made – but I wouldn’t describe them as a true picture of life. The questions are always, is it true? Is it interesting? To worry about those mandatory scenes that some people think make a picture is often just pandering to some conception of an audience. Some films try to outguess an audience. They try to ingratiate themselves, and it’s not something you really have to do. Certainly audiences have flocked to see films that are not essentially true, but I don’t think this prevents them from responding to the truth.

- I believe that drugs are basically of more use to the audience than to the artist. I think that the illusion of oneness with the universe, and absorption with the significance of every object in your environment, and the pervasive aura of peace and contentment is not the ideal state for an artist. It tranquilizes the creative personality, which thrives on conflict and on the clash and ferment of ideas. The artist’s transcendence must be within his own work; he should not impose any artificial barriers between himself and the mainspring of his subconscious. One of the things that’s turned me against LSD is that all the people I know who use it have a peculiar inability to distinguish between things that are really interesting and stimulating and things that appear to be so in the state of universal bliss that the drug induces on a “good” trip. They seem to completely lose their critical faculties and disengage themselves from some of the most stimulating areas of life. Perhaps when everything is beautiful, nothing is beautiful.

- I haven’t come across any recent new ideas in film that strike me as being particularly important and that have to do with form. I think that a preoccupation with originality of form is more or less a fruitless thing. A truly original person with a truly original mind will not be able to function in the old form and will simply do something different. Others had much better think of the form as being some sort of classical tradition and try to work within it.

- The destruction of this planet would have no significance on a cosmic scale.

- A filmmaker has almost the same freedom as a novelist has when he buys himself some paper.

- Perhaps it sounds ridiculous, but the best thing that young filmmakers should do is to get hold of a camera and some film and make a movie of any kind at all.

- I don’t think that writers or painters or filmmakers function because they have something they particularly want to say. They have something that they feel. And they like the art form; they like words, or the smell of paint, or celluloid and photographic images and working with actors. I don’t think that any genuine artist has ever been oriented by some didactic point of view, even if he thought he was.

- The criminal and the soldier at least have the virtue of being against something or for something in a world where many people have learned to accept a kind of grey nothingness, to strike an unreal series of poses in order to be considered normal…. It’s difficult to say who is engaged in the greater conspiracy – the criminal, the soldier, or us.

- I’ve got a peculiar weakness for criminals and artists, neither takes life as it is. Any tragic story has to be in conflict with things as they are.

- I’ve never achieved spectacular success with a film. My reputation has grown slowly. I suppose you could say that I’m a successful filmmaker – in that a number of people speak well of me. But none of my films have received unanimously positive reviews, and none have done blockbuster business.

- I believe Ingmar Bergman, Vittorio De Sica and Federico Fellini are the only three filmmakers in the world who are not just artistic opportunists. By this I mean they don’t just sit and wait for a good story to come along and then make it. They have a point of view which is expressed over and over and over again in their films, and they themselves write or have original material written for them.

- Call it enlightened cowardice, if you like. Actually, over the years I discovered that I just didn’t enjoy flying, and I became aware of compromised safety margins in commercial aviation that are never mentioned in airline advertising. So I decided I’d rather travel by sea, and take my chances with the icebergs […] I am afraid of aeroplanes. I’ve been able to avoid flying for some time but, I suppose, if I had to I would. Perhaps it’s a case of a little knowledge being a dangerous thing. At one time, I had a pilot’s licence and 160 hours of solo time on single-engine light aircraft. Unfortunately, all that seemed to do was make me mistrust large aeroplanes.

- {on the complaint that his films were emotionally cold] I ought not to be regarded as a once happy man who has been bitten in the jugular and compelled to assume the misanthropy of a vampire.

- The screen is a magic medium. It has such power that it can retain interest as it conveys emotions and moods that no other art form can hope to tackle.

- How could we possibly appreciate the Mona Lisa if Leonardo [‘Leonardo Da Vinci’] had written at the bottom of the canvas, ‘The lady is smiling because she is hiding a secret from her lover’? This would shackle the viewer to reality, and I don’t want this to happen to 2001.

- If it can be written, or thought, it can be filmed.

- The great nations have always acted like gangsters, and the small nations like prostitutes.

- I think the big mistake in schools is trying to teach children anything, and by using fear as the basic motivation. Fear of getting failing grades, fear of not staying with your class, etc. Interest can produce learning on a scale compared to fear as a nuclear explosion to a firecracker.

- Art consists of reshaping life but it does not create life, nor cause life.

- Anyone who has ever been privileged to direct a film also knows that, although it can be like trying to write ‘War and Peace’ in a bumper car in an amusement park, when you finally get it right, there are not many joys in life that can equal the feeling.

- I would not think of quarreling with your interpretation nor offering any other, as I have found it always the best policy to allow the film to speak for itself.

- A film is – or should be – more like music than like fiction. It should be a progression of moods and feelings. The theme, what’s behind the emotion, the meaning, all that comes later.

- I never learned anything at all in school and didn’t read a book for pleasure until I was 19 years old.

Stanley Kubrick Important Facts

- $10,000,000

- While working with Ian Watson on the story for A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001), Kubrick asked Watson for a pre-print copy of his Warhammer 40,000 tie-in novel Inquisitor. Watson quotes Kubrick as saying, “Who knows, Ian? Maybe this is my next movie?”.

- On November 1, 2006, Kubrick’s son-in-law Philip Hobbs announced that he would be shepherding a film treatment of Lunatic at Large. Kubrick had commissioned the project for treatment from noir pulp novelist Jim Thompson in the 1950s, but it had been lost until Hobbs uncovered a manuscript following Kubrick’s death. As of August 2011, this project is in development for future release, with the involvement of Scarlett Johansson and Sam Rockwell, and U.K. screenwriter Stephen Clarke.

- Kubrick once deliberated on adapting Robert Marshall’s novel All the King’s Men, a dramatic account of a British intelligence service operation during World War II.

- Kubrick was fascinated by the career of Nazi filmmaker Veit Harlan, his wife’s uncle, and contemplated creating a film of the social circle that surrounded Joseph Goebbels. Although Kubrick worked on this project for several years, the director was unable to progress beyond a rough story outline.

- In 1976, Kubrick sought out a film idea that concerned the Holocaust and tried to persuade Isaac Bashevis Singer to contribute an original screenplay. Kubrick requested a “dramatic structure that compressed the complex and vast information into the story of an individual who represented the essence of this man-made hell.” However, Singer declined, explaining to Kubrick, “I don’t know the first thing about the Holocaust.” In the early 1990s, Kubrick nearly entered the production stage of a film adaptation of Louis Begley’s Wartime Lies, the story of a boy and his aunt as they are in-hiding from the Nazi regime during the Holocaust-the first-draft screenplay, entitled Aryan Papers, was penned by Kubrick himself. Full Metal Jacket (1987) co-screenwriter Michael Herr reports that Kubrick had considered casting Julia Roberts or Uma Thurman as the aunt; eventually, Johanna ter Steege was cast as the aunt and Joseph Mazzello as the young boy. Kubrick traveled to the Czech city of Brno, as it was envisaged as a possible filming location for the scenes of Warsaw during wartime, and cinematographer Elemér Ragályi was selected by Kubrick to be the director of photography. Kubrick’s work on Aryan Papers eventually ceased in 1995, as the director was influenced by Schindler’s List (1993). According to Kubrick’s wife Christiane an additional factor in Kubrick’s decision was the increasingly depressing nature of the subject as experienced by the director. Kubrick eventually concluded that an accurate Holocaust film was beyond the capacity of cinema and returned his attention to A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001).

- In the early 1960s, Kubrick, a keen listener of BBC Radio, heard the radio serial drama Shadow on the Sun; written by Gavin Blakeney, Shadow on the Sun is a work of science fiction in which a virus is introduced to earth through a meteorite landing. At a time when Kubrick was looking for a new project, the director became reacquainted with Shadow on the Sun. Kubrick purchased screen rights from Blakeney in 1988 for £1,500. Thereon, Kubrick read and annotated a script before moving onto A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001). The tone of the unrealized project, as described by Anthony Frewin in The Kubrick Archives, is a cross between War of the Worlds and Mars Attacks! (1996).

- After the success of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Kubrick planned a large-scale biographical film about Napoleon Bonaparte. He conducted research, read books about the French emperor, and wrote a preliminary screenplay which has since become available on the internet. With the help of assistants, he meticulously created a card catalog of the places and deeds of Napoleon’s inner circle during its operative years. Kubrick scouted locations, planning to film large portions of the film on location in France, in addition to the use of United Kingdom studios. The director was also going to film the battle scenes in Romania and had enlisted the support of the Romanian army; senior army officers had committed 40,000 soldiers and 10,000 cavalrymen to Kubrick’s film for the paper costume battle scenes. In a conversation with the British Film Institute, Kubrick’s brother-in-law Jan Harlan stated that, at the time, the film was ready to enter the production stage and David Hemmings was Kubrick’s favored choice to play the character of Napoleon, while Audrey Hepburn was his preference for the role of Josephine. Although Jack Nicholson was cast in the role. In notes that Kubrick wrote to his financial backers, preserved in the book The Kubrick Archives, Kubrick expresses uncertainty in regard to the progress of the Napoleon film and the final product; however, he also states that he expected to create “the best movie ever made.” Napoleon was eventually cancelled due to the prohibitive cost of location filming, the Western release of War and Peace (1966), and the commercial failure of Waterloo (1970). A significant portion of Kubrick’s historical research would influence Barry Lyndon (1975), the storyline of which ends in 1789, approximately fifteen years prior to the commencement of the Napoleonic Wars. In March 2013, Steven Spielberg announced his intention to create, in conjunction with Kubrick’s family, a television miniseries based on Kubrick’s screenplay.

- In between Eyes Wide Shut (1999) and A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001), Kubrick was interested in making a film, for children and young adults, based on the viking epic novel, Eric Brighteyes.

- A number of screenplays that were written by Kubrick, who was either hired on a commission basis or was writing for his own projects, remain unreleased. One such screenplay is The German Lieutenant (co-written with Richard Adams), in which a group of German soldiers embark upon a mission during the final days of World War II. Other examples of unreleased Kubrick screenplays are I Stole 16 Million Dollars, a fictional account of early 20th century Baptist minister turned safecracker Herbert Emmerson Wilson (the film was to be produced by Kirk Douglas’ company “Bryna”, despite Douglas’ belief that the script was poorly written, and Cary Grant was approached for the lead role); and a first draft of a script about the Mosby Rangers, a Confederate guerrilla force that was active during the American Civil War. Kubrick was also interested in adapting to the screen Flowers in the Attic by V.C. Andrews, but it was cancelled due for the explicit incestuous relationship between the two main characters.

- In 1956, after MGM turned down a request from Kubrick and his producer partner James B. Harris to film Paths of Glory (1957), MGM then invited Kubrick to review the studio’s other properties. Harris and Kubrick discovered Stefan Zweig’s novel The Burning Secret, in which a young baron attempts to seduce a young Jewish woman by first befriending her twelve-year-old son, who eventually realizes the actual motives of the baron. Kubrick was enthusiastic about the novel and hired novelist Calder Willingham to write a screenplay; however, Production Code restrictions hindered the realization of the project. Kubrick had previously expressed interest in adapting a Willingham novel Natural Child, but was also prevented by the Production Code on that occasion.

- Following a 2010 announcement about the development of the Lunatic at Large project, plans for the prospective production of two other unrealized Kubrick projects were also announced. As of August 2012, Downslope and God Fearing Man were in development by Philip Hobbs and producer Steve Lanning, in partnership with independent company Entertainment One (eOne). A press release described Downslope as an “epic Civil War drama”, while God Fearing Man is the “true story of Canadian minister Herbert Emerson Wilson.”.

- In 2016, longtime assistant of Kubrick’s, Emilio D’Alessandro addressed that prior to his death, Kubrick was considering making a movie of Pinocchio. D’Alessandro said that Kubrick sent him to buy Italian about the subject. “He wanted to make it in his own because so many Pinocchios have been made. He wasted to do something really big… He said; ‘It would [be] very nice if I could make children laugh and feel happy making this Pinocchio.'” (Kubrick eventually used the project based on Brian Aldiss short story as his “Pinocchio film.”) D’Alessandro also stated that Kubrick’s lifelong fascination in World War II led to an interest in The Battle of Monte Cassino. D’Alessandro said, “Stanley said that would be an interesting film to make. He asked me to get hold of things … like newspaper cuttings and find out the distance from the airport, train stations. He had a friend who actually bombarded Monte Cassino during the war … It is horrible to remember those days. Everything was completely destroyed.”.

- Following J.R.R. Tolkien’s sale of the film rights for The Lord of the Rings to United Artists in 1969, The Beatles considered a corresponding film project and approached Kubrick as a potential director; however, Kubrick turned down the offer, explaining to John Lennon that he thought the novel could not be adapted into a film due to its immensity. The eventual director of the film adaptation Peter Jackson further explained that a major hindrance to the project’s progression was Tolkien’s opposition to the involvement of the Beatles.

- In a March 2013, Tony Frewin, Kubrick’s assistant for many years, wrote in an article in The Atlantic: “He [Kubrick] was limitlessly interested in anything to do with Nazis and desperately wanted to make a film on the subject.” The article included information on another Kubrick World War II film that was never realized, based on the life story of Dietrich Schulz-Koehn, a Nazi officer who used the pen name “Dr. Jazz” to write reviews of German music scenes during the Nazi era. Kubrick had been given a copy of the Mike Zwerin book Swing Under the Nazis (the front cover of which featured a photograph of Schulz-Koehn) after he had finished production on Full Metal Jacket (1987). However, a screenplay was never completed and Kubrick’s film adaptation plan was never initiated (the unfinished Aryan Papers was a factor in the abandonment of the project).

- Kubrick considered adapting Patrick Süskind’s novel Perfume, which he had enjoyed; however, the idea was never acted upon. The novel was later adapted for the screen by Tom Tykwer, as Perfume: The Story of a Murderer (2006).

- Kubrick’s wife and Jan Harlan, founders of the Stanley Kubrick Estate feel that Michael Herr’s book on the director is the most accurate personal account and Alison Castle’s book by Taschen is the most comprehensive.

- Kubrick loved animals. When he died, he had a Highland Terrier. seven Golden Retrievers. one Scotch Terrier, eight cats, and four Fern Donkeys.

- Shares his birthday with famed psychologist Carl Jung whose work is cited in “Full Metal Jacket”.

- Among his eccentricities was calling people multiple times a day whenever he had an idea about something, even if it was in the middle of the night. Kubrick himself was a night owl who rarely slept more than a few hours.

- He was known for being a perfectionist, although he denied this. He’d kept doing takes because he felt that his actors, even though they got the right idea, he thought they weren’t happy. When the Shining came out, there was a scene in the ending with Wendy and Danny in the hospital but Kubrick hated it and asked it to be removed just after a week after its release. Dorian Harewood, who played Eightball From Full Metal Jacket, said in an interview that Kubrick was a perfectionist. Kubrick called Harewood a few days later denying that he was a perfectionist.

- Resisted conceptual analysis of his films, stating that he didn’t want to have to explain what his films meant, and that he wanted each film to be judged on its own and not in his body of work. He further claimed that his method consisted simply of finding stories that interested him and trying to not repeat himself.

- Was a close friend of Steven Spielberg.

- Despite being known for his meticulous methods of filming, he was quite prolific in his earlier years. Beginning with Fear and Desire (1953) and ending with Barry Lyndon (1975), the average time between his films was two years. His last three films took much longer to complete. It took him five years to complete and release The Shining (1980), seven years to complete Full Metal Jacket (1987), and a whopping 12 years to complete Eyes Wide Shut (1999).

- When Kubrick bought Simon Cowell’s childhood home, he turned the entire ground floor into a private cinema.

- Wore a suit and tie every day while directing until the 1970s, when he began to dress in casual work clothes. His wife claimed he didn’t like choosing what to wear, and had a wardrobe full of identical shirts and pants.

- One of his favorite films was Eraserhead (1977) directed by David Lynch.

- A heavy chain smoker in his youth, he mostly quit smoking in the 1970s (his forties), but would still smoke occasionally under the pressure of his shoots. On the other hand, he was said to rarely ever drink alcohol.

- While working for, One-Eyed Jacks (1961), in Brando’s home, Brando asked visitors to remove their shoes so as not to scratch the wooden floor. Kubrick often removed his pants as well, choosing to work in nothing but his shirt and underwear.

- His father was born in New York, to an Austrian Jewish father, Elias Kubrick, and a Romanian Jewish mother, Rosa Spiegelblatt. His mother was also born in New York, to an Austrian Jewish father, Samuel Perveler, and a Russian Jewish mother, Celia Siegel.

- Used to skip school to take in double-features at the cinema.

- Legendary director Billy Wilder was a great admirer of Kubrick, and claimed that Kubrick “never made a bad picture.” Wilder also once told Cameron Crowe that the first half of Full Metal Jacket was “the best picture I’ve ever seen.”.

- First grew his famous beard during the making of “2001:A Space Odyssey”. He kept the beard for the rest of his life and kept his hair long.

- Shares his birthday with ‘Peter Hyams’, who directed 2010 (1984), sequel of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), which is directed by Kubrick.

- Claimed that his IQ was below average. It was rumored, however, that his IQ was around 200.

- Shared a love of photography and home movie making with Peter Sellers and they would often photograph each other at work.

- In the 5th edition of 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die (edited by Steven Jay Schneider), 9 of Kubrick’s films are listed. He is the director with the greatest percentage of films listed, since Kubrick made only 13 feature films. His listed films are Paths of Glory (1957), Spartacus (1960), Lolita (1962), Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), A Clockwork Orange (1971), Barry Lyndon (1975), The Shining (1980) and Full Metal Jacket (1987).

- A few days before his abrupt death, he revealed his least and most favorite personal films. He labeled Fear and Desire (1953) as his least favorite personal film, and Eyes Wide Shut (1999) as his most favorite personal film.

- In 1969, after the success of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Kubrick turned to one of his life-long obsessions into a motion picture screenplay – Napoleon. The script would have required an extremely large budget to be made into a film, and it was all on its way well into pre-production, when the studio suddenly decided to pull the plug after another big-budget biopic on the life of Napoleon, Waterloo (1970), failed financially. Kubrick, angry and depressed that his film was canceled, would later in his career (and even in the production of other films) attempt to get the project back on its feet with different companies over the years. The requirements needed would have been to write a completely new screenplay, and Kubrick, feeling he couldn’t match the masterpiece that was his original draft, dropped the project.

- In 1963 he was asked by the US publication Cinema to compile a list of his favorite films. They were: I Vitelloni (1953) (Federico Fellini, 1953), Wild Strawberries (1957) (“Wild Strawberries” USA title, Ingmar Bergman, 1958), Citizen Kane (1941) (Orson Welles, 1941), The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948) (John Huston, 1948), City Lights (1931) (Charles Chaplin, 1931), Henry V (1944) (“Henry V” USA title, Laurence Olivier, 1945), La Notte (1961) (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1961), The Bank Dick (1940) (W.C. Fields, 1940), Roxie Hart (1942) (William Wellman, 1942), Hell’s Angels (1930) (Howard Hughes, 1930).

- According to his daughter, Vivian Kubrick, the family name is pronounced like “Que-brick,” rather than like “koo-brick”.

- Grew up in the Bronx.

- Has directed two actors in Oscar-nominated roles: Peter Sellers (Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964)) and Peter Ustinov (Spartacus (1960)). Ustinov won his Oscar.

- His favorite cartoon character was Woody Woodpecker. Kubrick reportedly loved Woody Woodpecker so much that he wanted to feature him in every film he ever made (similar to what George Pal did) but Walter Lantz creator of Woody Woodpecker refused. In the final interview Lantz did he stated that he didn’t regret his decision when he saw films like The Shining (1980) or A Clockwork Orange (1971), but he did regret the decision when he saw films like 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) or Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964).

- According to Kirk Douglas, Kubrick allegedly wanted to take credit for the Spartacus (1960) screenplay that was primarily written by Dalton Trumbo. Trumbo, who was blacklisted at the time, originally was going to use the alias Sam Jackson. During the production of the film, Otto Preminger announced he had hired Trumbo to write the screenplay for Exodus (1960). Douglas, in turn, announced that he had been the first to hire Trumbo, who would be credited on his film. Preminger’s film was released six months earlier than “Spartacus,” which was released in October 1960. Douglas later said he decided to give Trumbo credit because he was appalled at Kubrick’s attempt to hog the credit. This “recollection” likely was colored by the fact that Kubrick went on to become a great director, and the film was seen as a Kubrick film rather than as the product of Kirk Douglas, who produced it. Douglas viewed the film as a fulfillment of his personal vision. It is highly unlikely that Kubrick would try to take the credit, as Trumbo served as one of the members of the film’s executive committee – screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, executive producer Kirk Douglas and producer Edward Lewis,” according to Duncan L. Cooper’s 1996 article “Who Killed ‘Spartacus’?” Trumbo was a friend of Edward Muhl, the boss of Universal Pictures. which was financing the film. According to Cooper, Howard Fast, a former Communist Party member who wrote the novel the film is based on, worked on the screenplay but received no credit. Walter Winchell had already revealed that Trumbo was working on the film, and it was widely known that Trumbo had won an Oscar using the pseudonym Robert Rich on The Brave One (1956), and that his “front”, Ian McLellan Hunter, had won an Oscar for the story of Roman Holiday (1953) that Trumbo had, in fact, written. In other words, the blacklist was a sham. There were rumors that the House Un-American Activities Committee was going to investigate the movie industry again, and right-wingers began attacking the film. Douglas gave into studio boss Muhl’s idea that the class conflict at the heart of Spartacus (1960) be muted, thus betraying both Trumbo’s screenplay and Fast’s novel. A major battle scene showing the triumph of Spartacus’ slave army over the Romans was deleted lest it seem too provocative, and medium and closeup shots of Laurence Olivier that showed his character – Roman dictator Crassus – experiencing fear over the slave rebellion were replaced with wide shots. Scenes where the slave army was crushed, of course, remain, though their length was cut back to minimize the carnage of the original 197-minute cut. Part of what remains – Olivier’s Crassus looking for Spartacus’ body among the living and the dead slaves – is shot indifferently on a sound stage and seems mismatched with the rest of the scene. Trumbo himself realized the necessity of muting his own passions in order to make the screenplay moderate so the film would be a success at the box office. He told an interviewer, “If the film had failed, neither I nor any other blacklisted writer would ever have been able to work again.” The actions of Preminger and Douglas to give Trumbo credit effectively ended the blacklist, though many blacklisted screenwriters continued to write under pseudonyms until the early 1970s.

- He joined with directors Martin Scorsese, Woody Allen, Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg, Robert Redford, Sydney Pollack and George Lucas in forming the Film Foundation (promotes restoration and preservation of film – May 1990).

- Out of all of his feature films, Spartacus (1960) is the only one to which he hasn’t contributed in writing the screenplay.

- According to “The London Standard” (29 June 1999 edition), Kubrick left £66,000 in cash and his house, Childwickbury Manor in Hertfordshire, England, to his wife Christiane Kubrick in a 24-page will drawn up on 22 July 1974. He also left her £21,000 in personal property. Before his death, Kubrick established a minimum of two private trusts, the Stanley Kubrick Trust Number One and the Children’s Trust, in which his wealth was collected. Proceeds from the trusts will be distributed among his two children and one stepchild.

- He had no intention of having Anthony Burgess’ write the screenplay for A Clockwork Orange (1971), intending to do it himself. In fact, there is little that Kubrick added to Burgess’ work except for editorial decisions such as eliminating the second murder Alex commits in prison and replacing Billy Boy with Georgie as police constable Dim’s partner (the entire last chapter of the novel was jettisoned, but it had been in the American edition of the novel that Kubrick had first read. Americans, as Burgess reasoned, did not like to see their criminals reformed). The dialog was considered by many critics and cineastes as being lifted almost straight from the book (though there are enough differences to dismiss that as a valid criticism of Kubrick the screenwriter). This is the first of the two movies in which Kubrick has sole credit as screenwriter (Barry Lyndon (1975), which immediately followed A Clockwork Orange (1971) is the other). Kubrick was one of the first director-writers to actually take credit on a film. Going back to the beginnings of the film industry, directors had often participated in the writing of their films, but most did not take credit. It might have been the fact that Kubrick used less of Vladimir Nabokov’s credited screenplay and more of his own writing (and the improvisations of Peter Sellers) for Lolita (1962) that influenced him to become a credited screenwriter. Lolita (1962) was shot at the time that the “auteur” theory (which held the director was the main author of a film) was gaining prominence, and from Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964) onward Kubrick took credit as a screenwriter. Earlier, he had worked uncredited on the screenplays of Paths of Glory (1957) and One-Eyed Jacks (1961), which he had originally been hired by Marlon Brando to direct. As he was one of the greatest masters the cinema has ever had and truly was the author of his films, Kubrick likely was encouraged to go it alone on A Clockwork Orange (1971) and Barry Lyndon (1975) (which allegedly he shot in an improvisatory manner after reading sections of the novel, which he carried with him during shooting).

- In interviews upon with the release of his highly controversial A Clockwork Orange (1971), Kubrick cited The Ox-Bow Incident (1943) as the kind of movie he did NOT want to make when defending the use of an “evil” protagonist (Alex). Kubrick reasoned that The Ox-Bow Incident (1943) was bad art, as it took the stand that lynching was evil because innocent people might be lynched, not the stand that lynching (i.e, extra-judicial murder) was itself evil. He wanted Alex explicitly evil (thus, the jettisoning of the last chapter of the original novel, in which Alex is reformed; this chapter was not in the American edition that Terry Southern had given to Kubrick). Kubrick felt that an explicitly evil Alex underscores the point that the state’s invasion of the prisoner’s soul (turning him into a mechanical man, a “clockwork orange”) was evil whatever the guilt or innocent, and the level thereof, of the prisoner.

- He once called Ken Russell in the early 1970s but ended the conversation abruptly because, according to Russell, he had been frightened by a bee. He then called several days later to ask Russell where he had found the lovely English locations for his period films. Russell told him and Kubrick used the locations in his next film, Barry Lyndon (1975). Russell said, “I felt quite chuffed.”.

- He directed four of the American Film Institute’s 100 Most Greatest Movies: 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) at #15, Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964) at #39, A Clockwork Orange (1971) at #70, and Spartacus (1960) at #81.

- Kubrick had started pre-production on Full Metal Jacket (1987) in 1980, a full seven years before it was theatrically released. The success of similar films during that time (particularly Oliver Stone’s Platoon (1986) and John Irvin’s Hamburger Hill (1987)) left him a bit jaded, feeling like he had been beaten at his own game. This sentiment stayed with him in the early 1990s when he decided to shelve Aryan Papers, his adaptation of the Louis Begley novel Wartime Lies. Kubrick had completed the script and had done a large amount of pre-production work on Aryan Papers; Johanna ter Steege and Joseph Mazzello had been cast in the lead roles and locations had been scouted in Denmark, Czech Republic and Slovakia. Warners officially announced the project as Kubrick’s next film in April 1993 and it was scheduled for a December 1994 release. Around the same time Steven Spielberg was shooting Schindler’s List (1993), and Kubrick thought the Holocaust-based subject matter of the two projects was too similar. The shelving of this project helps to explain the 12-year gap between Full Metal Jacket (1987) and Eyes Wide Shut (1999).

- Used his favorite piece of music “Thus spoke Zaratustra” by Richard Strauss, recorded by Herbert von Karajan as the music score in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

- “I want you to be big — Lon Chaney big,” Kubrick instructed Vincent D’Onofrio during the filming of Full Metal Jacket (1987).

- Kubrick and his partner James B. Harris, during the development of Lolita (1962), hired Marlon Brando’s friend Carlo Fiore — whom Kubrick had worked with on the development of One-Eyed Jacks (1961) — to write a screenplay of Vladimir Nabokov’s novel “Kamera obskura,” which Fiore had optioned himself. Written in Russian in 1932, “Kamera obskura” was first translated into English around 1938 as “Camera Obscura” and again circa 1960 as “Laughter in the Dark.”) The book had elements in common with “Lolita,” and Kubrick — who was worried he was being hustled when Fiore approached him with the rights to the novel — tied up the production of a potential rival film by hiring Fiore. Nothing came of Fiore’s foray into film development, although Tony Richardson later made a movie of the novel with Nicol Williamson starring.

- In his 1974 memoir “Bud: The Brando I Knew,” ‘Carlo Fiore’ (I)– writing of his experience developing and working on the movie One-Eyed Jacks (1961) with his friend Marlon Brando – said that Kubrick had wanted to hire Spencer Tracy to play the character of Dad Longworth in the film. The part had already been cast with Karl Malden, and Brando countered that Malden was a fine actor. Kubrick agreed, but said that Malden played “losers” and the part needed a heavyweight to balance Brando’s character of Rio. Brando immediately vetoed the idea of Tracy and forbade any more discussion on the topic.

- Carlo Fiore, who was credited as an assistant to the producer on One-Eyed Jacks (1961) and helped develop the picture, wrote that the firing of Kubrick by Marlon Brando (who went on to direct the film) was perhaps inevitable, as there was only room for one “genius” on the picture. Brando had originally intended to direct the film himself, but Paramount Pictures pressured him to hire a director. Both Kubrick and Brando, at the time, were represented by Music Corp. of America (MCA).

- Abigail Rosen, who co-starred with Viva in Andy Warhol’s Tub Girls (1967), was the first door lady at Max’s Kansas City, a nightclub in New York City. She claims she had the honor of throwing Kubrick out of the club. “At first Mickey [Ruskin] hired me as the coat-check girl, but it was on the second floor and we were schlepping coats from downstairs to upstairs, and taking them back down where the people wanted to leave. It was not a good plan, besides which people would go up and steal coats. So we abandoned the whole idea and I became the door lady with Bob Russell. The embarrassing times were when Mickey asked us to kick somebody out. The philosophy behind it was that no one would beat on or abuse a woman. I was asked one night to kick Stanley Kubrick out. He was drunk and obnoxious and neither Mickey or I knew who he was. I said, ‘Sir, I think it’s time for you to leave now, you’re not going to be happy here.’ And he left. Then Mickey found out the next day who we had kicked out, and he yelled at me for not recognizing him. ‘That’s why I have you here,’ he said, ‘you’re supposed to know who these people are.'”.

- In 1950, after creating and publishing a photo essay for Look magazine on boxing, he used the proceeds from the sale to the magazine to make his first film, a 16-minute documentary on the same subject entitled Day of the Fight (1951).

- Starting with Lolita (1962), he independently produced all his films from his adopted home of England, UK.

- At the age of 16, he snapped a photograph of a news vendor in New York the day after President Franklin D. Roosevelt died. He sold the photograph to Look magazine, which printed it. The magazine eventually hired him as an apprentice photographer while he was still in high school.

- By the age of thirteen, he had become passionate about photography, chess and jazz drumming.

- Was an avid feline lover, once having 16 of them at one point. He would often let his cats lay around his editing room after filming completed as his way of making up for time he lost with them while he was working.

- Ranked #4 in Empire (UK) magazine’s “The Greatest directors ever!” [2005]

- Seven of his last nine films were nominated for Oscars. He was nominated for Best Director four consecutive times, for his pictures starting with Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964) and ending with Barry Lyndon (1975).

- According to biographer Michael Herr, Kubrick was often noted for wanting to stick to each word of dialogue without changing it or an actor adding lines of his own. The two exceptions were Peter Sellers (with whom he worked on Lolita (1962) and Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964)) and R. Lee Ermey (from Full Metal Jacket (1987)).

- He was a huge fan of the New York Yankees.

- Due to his poor grades in high school (67% average) he was not accepted to a university. Although he never enrolled, he would sit in during classes at Columbia University.

- He was considered to be a well-read man with an extreme attention to detail. For his aborted film project on Napoléon Bonaparte, he had one of his assistants go to various bookstores to acquire every book he could find on the French emperor, and he returned with well in excess of 100. Kubrick read them all and astonished his associates with his level of retention. When working on a battlefield scene, he even examined an historical painting of the battle so he could note exactly what the weather was in the painting and make sure to film the battle on a day with similar weather patterns.

- According to a biography, Kubrick’s wife finally convinced him once to take what she considered a long-overdue vacation. While vacationing, she noticed he was taking copious notes about something. When asked what he was writing, she discovered he was jotting some ideas down about a film project!

- Was a lackadaisical student with grades near the bottom of his class.

- Daniel Waters wrote the original 180 page screenplay for Heathers (1988) intending for Kubrick to direct it, as he believed Kubrick was the only director who could get away with making a three-hour high school film. Kubrick wasn’t interested, and when the film was made the screenplay was cut nearly in half, resulting in a 102-minute film.

- He considered Elia Kazan the best American director of all time. His list of favorite directors included at various times Federico Fellini, David Lean, Ingmar Bergman, Vittorio De Sica, François Truffaut, and Max Ophüls.

- According to his close friend Michael Herr, he watched The Godfather (1972) over ten times and said it was probably the greatest film ever made.

- He was a big fan of American sitcoms Seinfeld (1989), Roseanne (1988) and The Simpsons (1989). He was also a fan of American football and would have his friends in America tape games and send them to him. In addition to being a sports fan, he was fascinated by the craft of television commercials. He was particularly impressed by how they could effectively tell a story in 30 seconds.

- According to his wife Christiane Kubrick, he would screen every movie he could get ahold of. One of his favorites was The Jerk (1979). He considered making Eyes Wide Shut (1999) a dark sex comedy with Steve Martin in the lead. He even met with Martin to discuss the project.

- He was so reclusive that the press would make up wild stories about him. One such story was that he shot a fan on his property, and then shot him again for bleeding on the grass.

- He reportedly briefly considered leaving England for either Vancouver, Canada or Sydney, Australia.

- Often read about psychology, and knew how to manipulate his cast quite well. A fine example of this is with Shelley Duvall in The Shining (1980).

- Had an extensive and rich friendship with Malcolm McDowell during the filming of A Clockwork Orange (1971). After filming ended, Kubrick never contacted him again.

- People would come to his door looking for him, and as few people knew what he looked like, he would tell them that “Stanley Kubrick wasn’t home.”

- Kubrick’s favorite pastime was chess and he was said to be a master at it. Many crew members and actors found themselves on the losing end of chess matches with him.

- Was voted the 23rd Greatest Director of all time by Entertainment Weekly. He was the least prolific director on this list, having made only 16 films over the course of a 48 year career.

- Loved the work of Franz Kafka, H.P. Lovecraft, Carlos Saura, Max Ophüls, Woody Allen and Edgar Reitz (esp. Heimat – Eine deutsche Chronik (1984)), among many others.

- The only author that Kubrick worked with personally was Arthur C. Clarke for 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

- In addition to The Seafarers (1953) (shot for the Seafarers International Union), he may have directed another commissioned project in the early fifties, “World Assembly of Youth,” for the United Nations, documenting a UN-sponsored gathering in New York City of young people from throughout the world. No copy of the film has been found and it has never been conclusively proven that it even existed in the first place (as with “The Seafarers,” Kubrick never publicly acknowledged it).

- His dislike of his early film Fear and Desire (1953) is well known. He went out of his way to buy all the prints of it so no one else could see it.

- His next project after Eyes Wide Shut (1999) was to be A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001), which was taken over by Steven Spielberg. It is dedicated to Kubrick’s memory.

- The controversy around A Clockwork Orange (1971)’s UK release was so strong that Kubrick was flooded with angry letters and protesters were showing up at his home, demanding that the film never be shown in England again. He personally petitioned the studio to pull it from theaters, despite his legal inability to control a film after production. The studio, out of respect for Kubrick, eventually decided to pull the film out of theaters prematurely.

- One of the founders of the Directors Guild of Great Britain.

- Refused to talk about his movies on set as he was directing them and never watched them when they were completed.

- He had a well-known fear of flying, but he had to fly quite often early in his career. Because of his hysteria on planes, he simply tried to lessen the amount of times he flew. According to Malcolm McDowell, Kubrick listened to air traffic controllers at Heathrow Airport for long stretches of time, and he advised McDowell never to fly.

- Rarely gave interviews. He did, however, appear in a documentary made by his daughter Vivian Kubrick shot during the making of The Shining (1980). According to Vivian, he was planning on doing a few formal TV interviews once Eyes Wide Shut (1999) was released, but died before he could.

- Planned to direct a film called “I Stole 16 Million Dollars” based on notorious 1930s bank robber Willie Sutton. It was to be made by Kirk Douglas’ Bryna production company, but Douglas thought the script was poorly written. Kubrick tried to get Cary Grant interested, which must have proved to be a failure as well, since the film was never made.

- He wanted to make a film based on Umberto Eco’s novel “Foucault’s Pendulum” which appeared in 1988. Unfortunately, Eco refused, as he was dissatisfied with the filming of his earlier novel The Name of the Rose (1986) and also because Kubrick wasn’t willing to let him write the screenplay himself.

- Father-in-law of Philip Hobbs, stepfather of Katharina Kubrick, & brother-in-law of Jan Harlan.

Stanley Kubrick Filmography

| Title | Year | Status | Character | Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eyes Wide Shut | 1999 | Director | ||

| Full Metal Jacket | 1987 | Director | ||

| The Shining | 1980 | Director | ||

| Barry Lyndon | 1975 | Director | ||

| A Clockwork Orange | 1971 | Director | ||

| 2001: A Space Odyssey | 1968 | Director | ||

| Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb | 1964 | Director | ||

| Lolita | 1962 | Director | ||

| Spartacus | 1960 | Director | ||

| Paths of Glory | 1957 | Director | ||

| The Killing | 1956 | Director | ||

| Killer’s Kiss | 1955 | Director | ||

| The Seafarers | 1953 | Documentary short | Director | |

| Fear and Desire | 1953 | Director | ||

| Day of the Fight | 1951 | Documentary short | Director | |

| Flying Padre | 1951 | Documentary short | Director | |

| God Fearing Man | 2015 | TV Mini-Series written by – 1 episode | Writer | |

| Eyes Wide Shut | 1999 | screenplay | Writer | |

| Full Metal Jacket | 1987 | screenplay | Writer | |

| The Shining | 1980 | screenplay | Writer | |

| Barry Lyndon | 1975 | written for the screen by | Writer | |

| A Clockwork Orange | 1971 | screenplay | Writer | |

| 2001: A Space Odyssey | 1968 | screenplay | Writer | |

| Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb | 1964 | screenplay | Writer | |

| Lolita | 1962 | uncredited | Writer | |

| Paths of Glory | 1957 | screenplay | Writer | |

| The Killing | 1956 | screenplay | Writer | |

| Killer’s Kiss | 1955 | story | Writer | |

| Flying Padre | 1951 | Documentary short uncredited | Writer | |

| Eyes Wide Shut | 1999 | producer | Producer | |

| Full Metal Jacket | 1987 | producer | Producer | |

| The Shining | 1980 | producer | Producer | |

| Barry Lyndon | 1975 | producer | Producer | |

| A Clockwork Orange | 1971 | producer | Producer | |

| 2001: A Space Odyssey | 1968 | producer | Producer | |

| Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb | 1964 | producer | Producer | |

| Paths of Glory | 1957 | executive producer – uncredited | Producer | |

| Killer’s Kiss | 1955 | producer | Producer | |

| Fear and Desire | 1953 | producer | Producer | |

| Day of the Fight | 1951 | Documentary short producer | Producer | |

| Killer’s Kiss | 1955 | Cinematographer | ||

| The Seafarers | 1953 | Documentary short | Cinematographer | |

| Fear and Desire | 1953 | photographed by | Cinematographer | |

| Day of the Fight | 1951 | Documentary short | Cinematographer | |

| Flying Padre | 1951 | Documentary short | Cinematographer | |

| Eyes Wide Shut | 1999 | camera operator – uncredited | Camera Department | |

| The Spy Who Loved Me | 1977 | lighting advisor: tanker scenes – uncredited | Camera Department | |

| A Clockwork Orange | 1971 | camera operator – uncredited | Camera Department | |